Photo from Unsplash | SJ 📸

The following post does not create a lawyer-client relationship between Alburo Alburo and Associates Law Offices (or any of its lawyers) and the reader. It is still best for you to engage the services of a lawyer or you may directly contact and consult Alburo Alburo and Associates Law Offices to address your specific legal concerns, if there is any.

Also, the matters contained in the following were written in accordance with the law, rules, and jurisprudence prevailing at the time of writing and posting, and do not include any future developments on the subject matter under discussion.

AT A GLANCE:

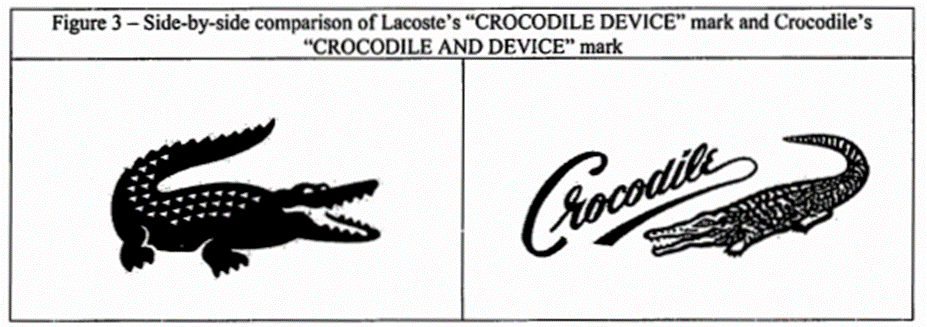

In deciding the trademark dispute between Lacoste and Crocodile International over the use of a crocodile device mark, the Supreme Court held that there exist distinct visual differences both in appearance and overall commercial impression between the marks which makes likelihood of confusion between them nil. The form, arrangement, general appearance, and overall presentation of their marks are evidently dissimilar, thus, the propensity to mistake one for the other is very low.

In the case of Lacoste S.A. v. Crocodile International PTE LTD., Lacoste lost its trademark dispute with Crocodile International (Crocodile) regarding the use of a crocodile device mark in the Philippines.

In giving due course to Crocodile’s trademark application, the Intellectual Property Office-Bureau of Legal Affairs (IPO-BLA) ruled that there is no confusing similarity between Lacoste’s and Crocodile’s marks, finding that since Crocodile’s mark is a composite mark, considering the word “Crocodile” in stylized font placed on top of the “saurian” figure, it has striking differences when compared to Lacoste’s mark.

On appeal, the IPO-Director General (IPO-DG) affirmed the IPO-BLA’s finding that there is no confusing similarity between Lacoste’s and Crocodile’s marks which would prevent the registration of the latter. The IPO-DG held that there is no dispute that both Lacoste and Crocodile had been using their respective marks – which have noticeable differences from each other – for a long time already, as in fact, they have been allowed to co-exist in various jurisdictions. Hence, goods which have Lacoste’ s marks can be easily associated with Lacoste, while goods having Crocodile’s marks can also be easily associated with Crocodile. This ruling was affirmed by the Court of Appeals, prompting Lacoste to file a petition for review on certiorari before the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court denied the petition and held that there are pronounced differences between Lacoste’s and Crocodile’s marks, which resultantly, make them distinguishable from one another.

The Court noted that Lacoste’s “saurian” figure is facing to the right, meaning the head is at the right side while the tail is at the left side, and is aligned horizontally. On the other hand, Crocodile’s “saurian” figure, is facing to the left, meaning the head is at the left side while the tail is at the right side. Furthermore, both the “saurian” figure and the word “Crocodile” in stylized format on top of it are tilted in that the right side’s alignment is higher than the left side. More significantly, the “saurian” figures in both marks are easily distinguishable from one another, considering that in Lacoste’ s mark, the “saurian” figure is solid, except for the crocodile scutes found on the body and the base of the tail which are depicted in white inverted triangles. There are also crocodile scutes protruding from the tail of Lacoste’s “saurian” figure. Meanwhile, the “saurian” figure in Crocodile’s mark is not solid, but rather, more like a drawing. Further, unlike Lacoste’s “saurian” figure, Crocodile’s “saurian” figure does not have crocodile scutes, whether protruding or not; and instead, is depicted with various scale patterns from the base of the head up to the tail.

Thus, the Supreme Court concluded that there exist distinct visual differences both in appearance and overall commercial impression between Lacoste’s and Crocodile’s marks which makes likelihood of confusion between them nil. The form, arrangement, general appearance, and overall presentation of their marks are evidently dissimilar, thus, the propensity to mistake one for the other is very low.

Lacoste also argued that the doctrine of trademark dilution is applicable in this case but the Supreme Court disagreed.

Levi Strauss & Co. v. Clinton Apparelle, Inc. instructs that trademark dilution has been defined as “the lessening of the capacity of a famous mark to identify and distinguish goods or services, regardless of the presence or absence of: (1) competition between the owner of the famous mark and other parties; or (2) likelihood of confusion, mistake or deception.” It further elucidates that trademarks are eligible for protection upon finding that: (1) the trademark sought to be protected is famous and distinctive; (2) the use by Crocodile of the mark began after the Lacoste’s mark became famous; and (3) such subsequent use defames Lacoste’ s mark.

A careful perusal of the records of this case reveals that Lacoste’s allegation of trademark dilution is merely speculative for lack of sufficient basis. While it is true that: (a) Lacoste’ s mark is considered as an internationally well-known mark; and (b) Lacoste had first used its mark in the global market in 1933, or years before Crocodile introduced its own mark in 1949, there is no showing that Crocodile in any way-at least on the basis of the evidence presented by Lacoste –defamed or disparaged Lacoste’s mark.

As a matter of fact, in adherence to their Mutual Co-Existence Agreement, Crocodile even facilitated the registration of Lacoste’s mark in different jurisdictions by giving consent to Lacoste’s entry in countries where Crocodile first registered its mark. It is further not amiss for the Court to point out that like Lacoste, Crocodile has taken great pains to acquire goodwill in favor of its mark through its long-established use and intensive promotion in different countries. The Court even sees no intent on the part of Crocodile to ride on the goodwill of Lacoste by reason of their long-standing co-existence with one another in different countries worldwide. All told, evidence is wanting as to Crocodile’s capacity to tarnish Lacoste’s mark or even an intent on its part to do so. Neither does Crocodile’s mark falsely suggest a connection with Lacoste’s mark so as to blur the distinctive quality of the latter.

RELATED ARTICLE:

- Memorandum Circular (MC) 2023-001: Updates trademark rules for protecting non-traditional marks and mandates online transactions

- The Supreme Court decides: A trademark registered in bad faith is considered as unfair competition under the IP Code.

Click here to subscribe to our newsletter

Alburo Alburo and Associates Law Offices specializes in business law and labor law consulting. For inquiries regarding legal services, you may reach us at info@alburolaw.com, or dial us at (02)7745-4391/ 0917-5772207/ 09778050020.

All rights reserved.